Psychological therapies based on the efficacy of their clinical outcomes

"I haven't seen my psychoanalyst in 200 years. He was a strict Freudian and if I'd seen him in all that time I'd be almost cured by now."

Woody Allen

What is the image people have of "doing therapy"? But also: is it appropriate to choose any type of therapy...?

It is difficult to answer question 1 with an answer that goes beyond a mere opinion, or a set of opinions drawn from a small sample of known people (whether they are therapists or not). However, it is easier to answer question 2, and perhaps thereby attempt to answer question 1.

There is the media and entertainment industry, and the recent digital streaming platforms, which inundate us with content, often associated with a presumed psychological world.

In general, the therapist is shown as someone who strokes his or her chin, takes notes, listens and "asks questions about life".

If it is a woman, she generally wears glasses and dresses somewhat executive.

The patient is shown as someone who has lost control or autopilot over his will, desires, fantasies and emotions.

Thus, we already have two great stereotypes: what we could call "the lay priestly listening" of the therapist, and an individual who has lost the government over his mind, the government of himself. What assumptions people make about what is "their mind" would lead us to an extremely difficult and unfinished reflection. But, as a tentative comment, we could say that people sometimes imagine their mind as the scenario of a video game, where everything is controllable from a series of commands. Sometimes, however, the scene can get out of control, or very unexpected things can emerge in the scene, and the commands become unresponsive or distorted. Some strange factor or mechanism has "hacked" our mind.

For many people the mind is something like an invisible, intangible gadget that can be manipulated without major consequences. But already the ancient Hellenes -such as the Stoics-, or figures like Buddha in the East, warned about these consequences based on imprudence or the excesses of the spirit.

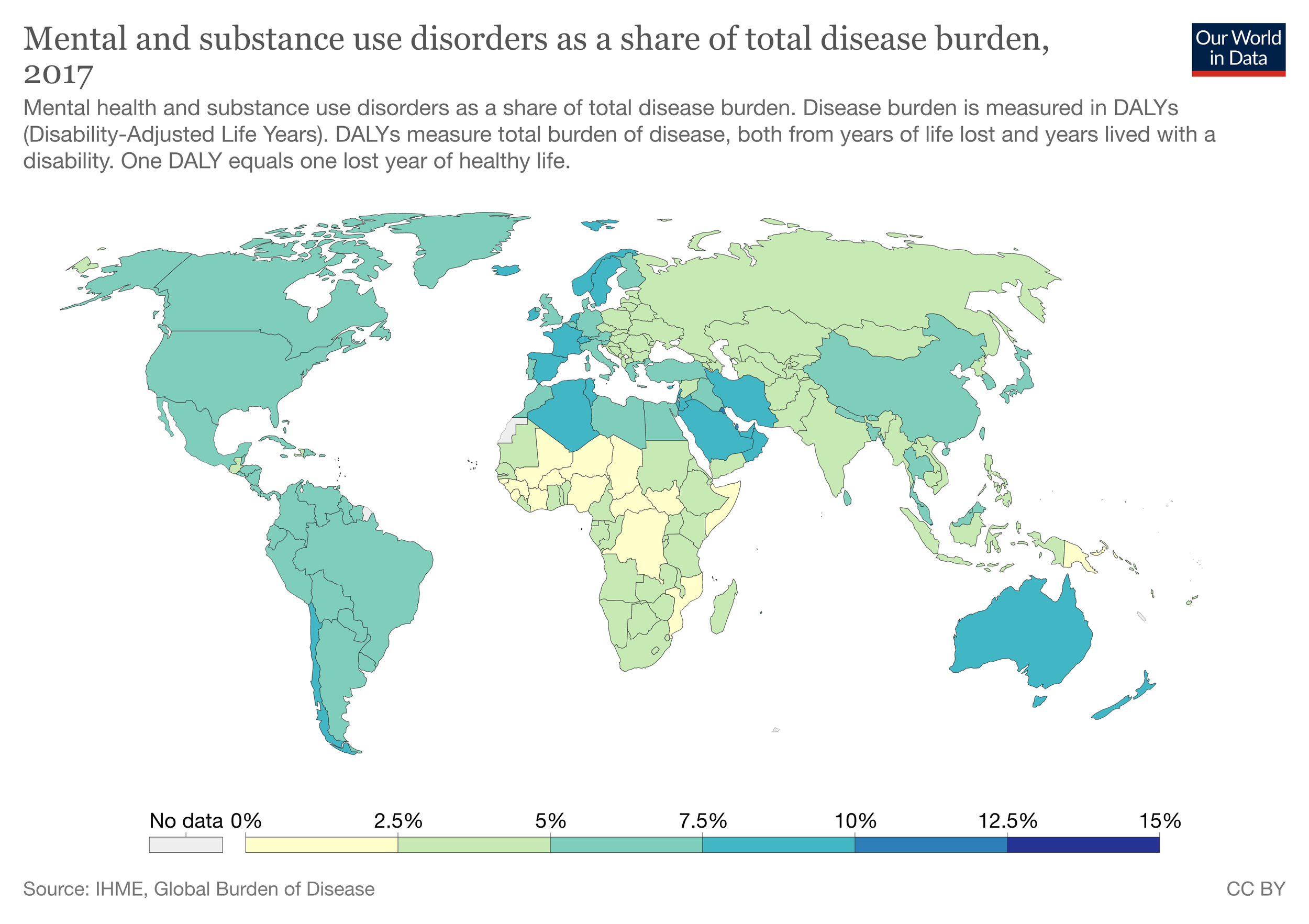

Be that as it may, for these problems that are as old as the history of the species itself (there is no serious scientific or common sense reason to suppose that ancient Hellenes did not suffer from mood disorders, that Vikings did not have emotionally disruptive behaviors, or that medieval peasants did not get depressed), the modern world has tried to provide answers as scientific as possible in the last 150 years, so "psychology" (which is far from being a unique field), is something very new in human cultural history. If we talk about mental conditions and problem behaviors, we are talking specifically about clinical psychology, which is only one area within psychology.

Types:

Within this short history (seen in historical perspective), psychoanalysis has been a landmark, and even its remnants are very powerful in areas such as the Rio de la Plata (Argentina, Uruguay), with multiple detachments, disseminations of all kinds of therapeutic models that, to some extent, would have theoretical components of psychoanalysis.

The truth is that, in much of the world, since the 1980s, psychoanalysis has tended to be ignored due to lack of empirical evidence about the effectiveness of its clinical approaches. Mentioning the already classic study "The Black Book of Psychoanalysis...", or Hans Eysenck's "Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire" implies a declaration of war for many, since psychoanalytic organizations continue to have lobbying power and their figures are invited to the media.

In North America, in the late 1970s, a team of experts led by Hans Strupp was given the task of investigating the negative effects of therapeutic approaches in institutions. It was a time when the use of public money had to be optimized as much as possible due to the fiscal deficit. What this research (1977) found was that many times, much more than desirable, psychotherapies in institutional contexts increased mental distress and ended up reinforcing the patients' problems. One of the main factors was that the therapeutic alliance of therapist/patient was not governed by any protocol model, but was left entirely to inventiveness, which often turned out to be arbitrary. At that time, most therapists came from psychodynamic models, largely clinical detachments from the original psychoanalysis. Moreover, they realized that it was necessary to define precisely what psychotherapy is: psychotherapy cannot be merely a helpful human intervention. In other words, what Strupp and his team were subtly saying is that the therapist cannot be an inspired counselor, a well-meaning lecturer, a guru or a charlatan. You are totally free to choose a guru; it is just a good idea to know that this is not psychotherapeutic treatment.

Hans Strupp